Ellipsis (Site #9)

Like a painful memory erased, suppressed or forgotten, an ellipsis is an omission, or incomplete sentence, silently acknowledged but not expressed, and so it remains in suspension, like clapping hands waiting for the end of a performance. The performers have all disappeared to an endless stream of clapping, all that remains are their shoes, ghosts floating in space, and yet their voices can be heard throughout time, passed on by the generations, a nightmare or a dream that refuses to leave us when we awake, remaining suspended between reality and the unconscious, absence and presence.

Ellipsis is a collaborative reflection on the unhealed wounds from decades of show trials and disappearances during the fifty years of communism in the former Czechoslovakia.

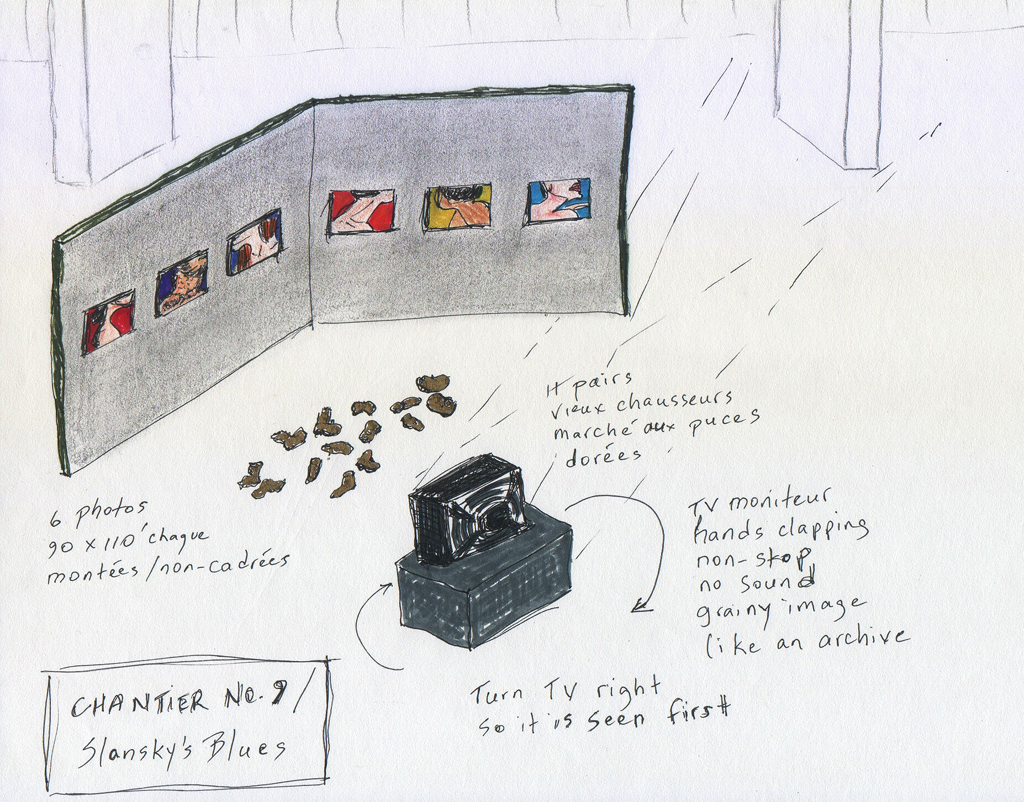

It assembles three works: Necks, photographs; Remnants, sculptures and photographs; The Show Must Go On, 8-mm archive film loop of hands clapping during a speech given by Stalin.

Ellipsis(from the Ancient Greek: ἔλλειψις, élleipsis, “omission” or “falling short”) is a series of dots that usually indicates an intentional omission of a word, sentence, or whole section from a text without altering its original meaning. Depending on their context and placement in a sentence, ellipses can also indicate an unfinished thought, a leading statement, a slight pause, a nervous or awkward silence.

In 1949 Stalin began to stage a series of mass events throughout Eastern Europe that would come to be known as the Show Trials. In courtroom scenes scripted to the point where if a prosecutor forgot a question the witness would answer it anyway, high-ranking Party officials were convicted of espionage and treason and then executed. The Show Trials were Stalin's attempt to terrorize the satellite Communist parties into absolute submission. They reached their zenith in Czechoslovakia, which, due to its large Communist Party and its special gratitude towards Moscow, had become the most Stalinist nation in the East Block.

The trials were the supreme manifestation of the paranoia that had gripped the Soviet Union for two decades; as socialism had declared itself scientifically perfect, any flaw must be the work of enemy agents. The factory manager who did not make his production quota could be shot as an "imperialist wrecker", and those who failed to volunteer for higher and higher production quotas – and there was clearly little incentive to do so - could be shot for the same crime. When the all-wise Stalin's name was mentioned at a gathering, all present stood and applauded. Applause would go on for ten minutes; one could be shot for being the first to stop clapping.

There was no more a slavishly loyal Stalinist than Slansky, but unfortunately for him, he was a Jew. On November 23, 1951, he was handcuffed, bound, gagged, and arrested, charged with "cosmopolitanism" and "Zionism". In prison Slansky tried to choke himself with his own hands. It took eight months to break him, but in July 1952, he signed a confession. Slansky and others edited and memorized their own death sentence. Their trial began November 20, 1952. Stalin had personally approved the script. All the defendants begged for the death penalty. The Party staged voting booths in factories, schools, offices, so that people could demand the death penalty for Slansky…. Even in the last letters the defendants were allowed to write to their families, they continued to thank their accusers, praise the Party, and confess their guilt. 'I got what I deserved', were Slansky's last words as he went to the gallows."

—Tina Rosenberg, The Haunted Land: Facing Europe’s Ghosts After Communism, pp 10-12

Veletrzni Palace, National Gallery Prague, 2001

With Film Academy of Performing Arts

Photographs, aluminum, shoes, enamel, TV monitors, video loop (8')